El 8 de septiembre de 1964, Miguel Lawler Fitzgerald completó la hazaña de su vida: aterrizó su avión monomotor Cessna 185 en las Islas Malvinas, plantó una bandera argentina y dejó una proclama reivindicando la soberanía nacional. Otros pilotos que lo habían intentado antes, fracasaron. Lo consiguió, casualmente, el día de su cumpleaños número 38. Voló solo, sentado sobre un tanque de combustible, con un bote inflable atado a su cuerpo.

La idea de volar a las islas siempre aparecía en las conversaciones entre pilotos, como un sueño compartido. En 1952, dos aviadores lo intentaron. Fitzgerald conocía su historia, sabía que llegaron a sobrevolar las islas pero no lograron descender por las fuertes corrientes de viento. Sin embargo, lo que más lo atormentaba fue enterarse de que, cuando regresaron a Comodoro Rivadavia, luego de siete horas de vuelo, los pilotos fueron sancionados: les quitaron su licencia y les prohibieron volar por un año.

Hubo un hecho preciso que empujó a Fitzgerald a la aventura: en septiembre de 1964, los diarios anunciaron que Naciones Unidas trataría en una sesión especial la descolonización de territorios en América Latina. Fitzgerald, que luego confesaría que venía rumiando la idea durante más una década, pensó que era el momento perfecto para hacer su acto de reivindicación.

No era un piloto improvisado: en 1962 estableció su primer récord personal al volar solo desde Nueva York hasta Buenos Aires sin escalas a bordo de un monomotor Cessna 210 (260 HP). En ese entonces, ni siquiera las grandes aerolíneas con sus imponentes flotas lograban hacer semejante trayecto sin detenerse.

Al Cessna que lo llevó a Malvinas lo bautizó “Luis Vernet” en honor al primer comandante político de las islas, previo a la invasión inglesa. Despegó el 6 de septiembre 1964 desde el aeródromo de Monte Grande rumbo a Trelew. Allí se reabasteció de combustible para llegar a Puerto Madryn, donde pasó la noche. Al día siguiente avanzó por Comodoro Rivadavia rumbo al sur, pero a la altura de Caleta Olivia el motor comenzó a fallar. Debió aterrizar “de emergencia” en Pico Trucando para solucionar un problema con las bujías. Una vez resuelto, siguió hasta Río Gallegos. Recién entonces comenzaría el verdadero desafío: atravesar más de 550 kilómetros de un mar de aguas frías y turbulentas para descender en las islas.

Para lograrlo, agregó dos tanques de combustible extra. Eso le daría una autonomía de 12 horas de vuelo. En Gallegos, con la complicidad del comandante y gerente de Austral Ignacio Fernández, consiguió toda la información técnica y meteorológica necesaria para llegar a las Islas. También coordinó con un operador de radio una frecuencia por la que Fitzgerald iría avisando su posición. En los registros, el destino de vuelo que declaró fue Ushuaia.

En la mañana del 8 de septiembre, el Cessna “Luis Vernet” despegó rumbo a las Islas Malvinas. Fitzgerald volaba a 8000 pies (2500 metros), debajo un interminable manto azul de agua helada. Su única compañía era la radio AM del avión donde sonaban tangos: Mi Buenos Aires Querido y otros clásicos. De acuerdo a su plan de vuelo, llegaría destino al mediodía. Después de tres horas y quince minutos, hizo contacto visual con las islas. Eran cientos de islas e islotes que formaban el archipiélago. Cuando se preparaba para aterrizar, una densa capa de nubes le impidió ver el suelo. Como sabía que estaba cerca de un cerro de 600 metros de altura, recobró altura y decidió esperar hasta encontrar un claro. Por radio avisó “a continente” que había encontrado lo que buscaba y que estaba cruzando el estrecho San Carlos, el canal que separa a las islas Soledad y Gran Malvina. Pasados unos minutos, la capa de nubes se abrió y pudo identificar Puerto Stanley (Puerto Argentino), en el noreste de la Isla Soledad.

Fitzgerald realizó dos virajes sobre el pueblo antes de aterrizar su avión en una pista precaria que se utilizaba para carreras de caballos. Antes de descender volvió a hacer contacto por radio, para avisar que había llegado a destino. Luego, sin apagar el motor, Fitzgerald bajó del avión con una bandera argentina, que era la que usaban en su casa para celebrar en las fechas patrias, y la colgó de un alambrado que encontró a pocos metros de la nave.

Un grupo de kelpers (nombre que pusieron los británicos a los malvinenses, derivado de un algo común en la región llamada “kelp”) que había visto al avión sobrevolar sus casas, se acercaron a Fitzgerald. Pensaron que estaba perdido o necesitaba ayuda. El argentino los saludó y les dio un papel. “Entréguenle esto a su gobernador”, les dijo.

“Al representante del gobierno ocupante de inglés Islas Malvinas. Yo, Miguel L. Fitzgerald, ciudadano argentino, único, necesario y suficiente título que exhibo en cumplimiento de una misión que está en el ánimo de veintidós millones de argentinos, llego al Territorio Malvínico para comunicarle la irrevocable determinación de quienes como yo han dispuesto poner término a la tercera invasión inglesa a territorio argentino...”, comenzaba el texto de su proclama.

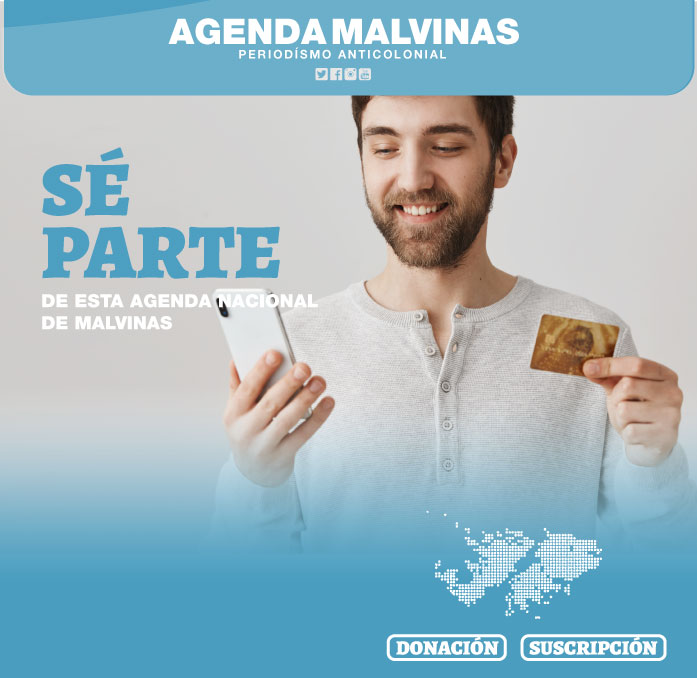

Concretada la entrega de la carta, Fitzgerald subió a su avión y despegó nuevamente rumbo a Río Gallegos. Mientras tanto, en la Argentina, el diario Crónica imprimía los ejemplares con la noticia: “MALVINAS, HOY FUERON OCUPADAS”. Ese día, no se habló de otra cosa.

Titular del diario Crónica sobre la hazaña de Fitzgerald y el recibimiento del piloto en la redacción junto a Héctor Ricardo García.

En enero de este año, el que contó cómo se enteró la prensa de la llegada de su padre a Malvinas, fue su hijo Christian:

-Aunque mi padre era una persona muy reservada y mantuvo su plan con total hermetismo, solo sabían mi madre, mi abuela y un par de personas más, antes de viajar él se contactó con la prensa. Estaba el antecedente de los que habían ido antes y les habían suspendido la licencia... y para él volar era su fuente de ingresos, el único recurso que tenía para alimentar a su familia, así que no podía darse el lujo de perder la licencia. También pensó en la posibilidad de que los ingleses lo detuvieran o negasen que él hubiese llegado a destino. Entonces mi padre primero fue al diario La Razón, pero no le dieron importancia. De ahí fue a ver al dueño del diario Crónica, Héctor Ricardo García. Cuando García escuchó a mi padre, le gustó tanto la idea que ofreció alquilarle el avión y pagar el combustible. Además, le propuso contratar a un fotógrafo para que lo acompañase. Pero mi padre se negó porque el viaje implicaba ciertos riesgos y, con los combustibles de combustible extra, ya no quedaba lugar en la cabina. Él quería que su llegada a Malvinas se imprimiese en los diarios, que fuera noticia, para evitar consecuencias desagradables. Por precaución.

El vuelo coincidió con la fecha de su cumpleaños número 38. García había enviado un periodista a Río Gallegos para que le avisara cuando mi viejo llegase a Malvinas. Le advirtió que si llegaba el 8 de septiembre la noticia podía ser tapa, pero que el 9 no lo podía garantizar porque había un partido de fútbol importante.

La tarde del 8 de septiembre de 1964, en la aeroestación del aeropuerto de Río Gallegos; relatando su hazaña

-¿Qué sucedió cuando su padre aterrizó en Río Gallegos?

-Hubo revuelo. Antes de partir rumbo a Buenos Aires, la Fuerza Aérea le abrió un sumario. Hizo una primera parada en Bahía Blanca, donde pasó la noche, y luego hizo escala en Azul. Ahí tuvo el primer reconocimiento: le entregaron una corona de flores en nombre del Partido Radical, pero mi padre no la aceptó. Dijo que su causa era “nacional” y continuó el viaje a Capital.

-¿Cómo fue la llegada a la ciudad de Buenos Aires?

-Había una multitud esperándolo en Aeroparque. “El hombre de Malvinas”, decían los medios. Cuando bajó, se abrazó con Ciro Comi, que fue quien le prestó el avión para la travesía. Le dijo: “Todo bien, viejo. ¡Salvados los veintidós mil dólares!”. Se refería al precio del Cessna. Lo llevaron en andas hasta un jeep rojo y lo pasearon por la ciudad: la avenida Figueroa Alcorta, Retiro, Plaza de Mayo... todos lo vitoreaban. La caravana terminó en la sede del diario Crónica. En la redacción lo esperaba toda su familia. Fue un suceso importante.

“Desde 1833 hasta mi vuelo, hubo todo un largo siglo donde solo hubo escritos diplomáticos, seguramente muy bien redactados, pero que no condujeron a nada. Lo mío fue algo concreto, por eso se destaca. Yo, en cierta manera he encendido la mecha, ahora les toca a ustedes seguir avivando ese fuego para que no se extinga...La cuestión de Malvinas no es un problema económico, pues un millón de ovejas no nos afecta; es un problema de dignidad y no podemos quedarnos de brazos cruzados cuando se nos quita una parte de territorio”, dijo Miguel Fitzgerald en una entrevista el 30 de septiembre de 1964.

-Finalmente, ¿lo sancionaron?

-No, tuvo tanta repercusión y aceptación popular que solo fue apercibido. Días después, el presidente Arturo Illia lo invitó a una audiencia.

-¿Cuáles fueron las repercusiones del vuelo?

-Mi padre siempre dijo que logró lo que quería, que su vuelo coincidiera con la fecha en la que la ONU trataba el tema de Malvinas y tuviera difusión en los medios. A partir de ese hecho, Londres decidió establecer en las islas un contingente permanente de Royal Marines. Y hasta ese momento los malvinenses no sabían que existía un reclamo argentino sobre las islas.

Luego del aquel vuelo histórico, Fitzgerald fue invitado a dar charlas por todo el país. En su casa recibió centenares de cartas felicitándolo por su valentía. Si hasta el autor de La Marcha de Malvinas le obsequió una partitura original con la dedicatoria: “Al señor Miguel Fitzgerald, primer abanderado de Las Malvinas. Cordialmente, el autor José Tieri, 12/6/1966″.

Tras su merecido momento de fama, Miguel Fitzgerald retomó su antiguo trabajo: traslado de pasajeros y flete de aeronaves desde los Estados Unidos.

Quién era Miguel Fitzgerald

Miguel Fitzgerald nació el 8 de septiembre de 1926. Era el menor de dos hijos de un matrimonio de irlandeses que había llegado al país a principios del siglo pasado. Parte de su infancia vivió en Guaminí, localidad ubicada al oeste de la provincia de Buenos Aires. Luego, cuando su padre falleció, entró como pupilo al colegio San Cirano, en Buenos Aires. Finalmente, su madre se mudó a la Capital Federal y Miguel terminó el secundario en la Escuela Técnica Otto Krause, donde se recibió de técnico mecánico.

Regreso a Malvinas como piloto Crónica

Años después del viaje a Malvinas, Miguel Fitzgerald fue contratado por Crónica como piloto oficial del diario. Le dieron un Cessna LV-ILU, modelo U206, con el que llevaba a periodistas y fotógrafos a realizar todo tipo de coberturas. Cubrió inundaciones, accidentes, carreras, partidos de fútbol, la muerte del “Che” Guevara... pero tal vez la nota más significativa para él fue su regreso a las Islas Malvinas.

-En noviembre de 1968. Crónica ya tenía un avión más grande, un Aerocomander, que es un avión de dos motores, y García le dijo a mi padre que quería que lo llevase a Malvinas para cubrir la noticia de un grupo de diplomáticos británicos que viajaría a las Islas. La expedición estaba encabezada por el ministro de Asuntos Exteriores, Lord Chalfont.

-Salieron de Aeroparque rumbo a Río Gallegos, y desde ahí volaron a Malvinas. Instalaron tanques de combustible en el interior de la aeronave para asegurar el abastecimiento para el regreso. Viajaron mi padre, García y el periodista Carlos Nava. Cuando sobrevolaron las islas descubrieron que habían puesto barricadas sobre la pista de cuadreras. Evidentemente, sabían que alguien podía visitarlos. Comenzaron a sonar unas sirenas y dos helicópteros de la Marina Británica obligaron a mi padre a aterrizar.

Fue todo un poco accidentando, pero no hubo heridos. Cuando aterrizaron, apareció una dotación de 60 hombres armados que rodearon la aeronave y los llevaron detenidos. García explicó que había ido como periodista para entrevistar a Lord Chalfont y pidió hablar con él, pero no logró su propósito. Le confiscaron la máquina de escribir, la cámara de fotos y otros documentos. Al día siguiente los embarcaron en el Endurance, el buque patrullero antártico de la Marina de Guerra británica y los mandaron de regreso a la Argentina. Luego les devolvieron las pertenencias. Al avión lo desarmaron y lo enviaron de regreso a través de Montevideo.

Miguel Lawler Fitzgerald trabajó un tiempo más para Héctor Ricardo García. En los últimos años, fue piloto de su avión particular. Falleció el 25 de noviembre de 2010, a los 84 años.

Actualmente, el pequeño avión Cessna 185, en el que Miguel Fitzgerald logró llegar a las Islas, pende del techo del Museo Malvinas e Islas del Atlántico Sur.

Fuente:

La Nación